Text by Lisa Paulson and Cassandra Shore

Ahlan wa sahlan! Welcome to the world of Middle Eastern dance! Here you will find an introduction to the dance, the music, and the Arab cultures exemplified.

Middle Eastern music can sound strange at first to American ears, because the notes of the scales may often lie only a quarter-step apart, rather than a half-step. What may sound like dissonance is actually subtle difference in tone. Other characteristics include complex rhythms, use of improvisation and ornamentation, and a call-and-response form. Traditional Arab music does not utilize harmony in the Western sense (although accidental harmony may occur); each player, while playing in unison, presents a different attack to the notes, thus enriching the sound of the orchestra.

Here is Karim Nagi demonstrating the rhythms of the Levant. He is at the New Levant Initiative Conference on a music panel with Dr. A.J. Racy, Simon Shaheen, Lyth Sidiq, and Kareem Roustom at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts on March 1, 2018.

The Middle Eastern dancer embodies dance music, as body parts move to different rhythms. The dancer’s job is to express the human emotions driving the music, while increasing audience's awareness of music and feeling.

In a live music setting, when it all works together, Middle Eastern music and dance are inseparable art forms - the music drives the dance, while the dancer simultaneously influences the musicians. Many times, the dancer and the musicians are improvising around a central theme, similar to American jazz musicians.

The audience is the final piece of the puzzle, adding the sense of celebration and spontaneity that brings the performance to life. The audience can express their appreciation for the performers by clapping, saying "aiwa" (yes!), or making the traditional ululating cry called the zagroota (plural = zaghareet)! It's like an audience yelling "Bravo!" at the opera or "Olé!" to a flamenco dancer.

In the Arab world, dance and music are woven into the fabric of everyday life, a vital part of weddings, feast days, and family gatherings. Dance is practiced in every region of the Middle East, including Egypt, Turkey, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and North Africa. Middle Eastern dance also has related styles in Central Asia and draws from nomadic cultures such as the Bedouin and Romany (Gypsy).

There are three main styles of Arab Dance:

Folkloric dances are based on distinct regional styles. Examples range from the lively rhythms and colorful costumes of the Nubian dances of Upper Egypt; to the zar, a dramatic trance-dance ritual practiced across North Africa; to Khaleegy, a delicate, graceful dance from the Persian Gulf danced by women dressed in flowing beaded gowns, accompanied by female musicians; to the earthy fluttering pelvic movements of the Algerian Amazigh, accompanied by the folk instruments of the region, including chants, drums, and clapping percussions.

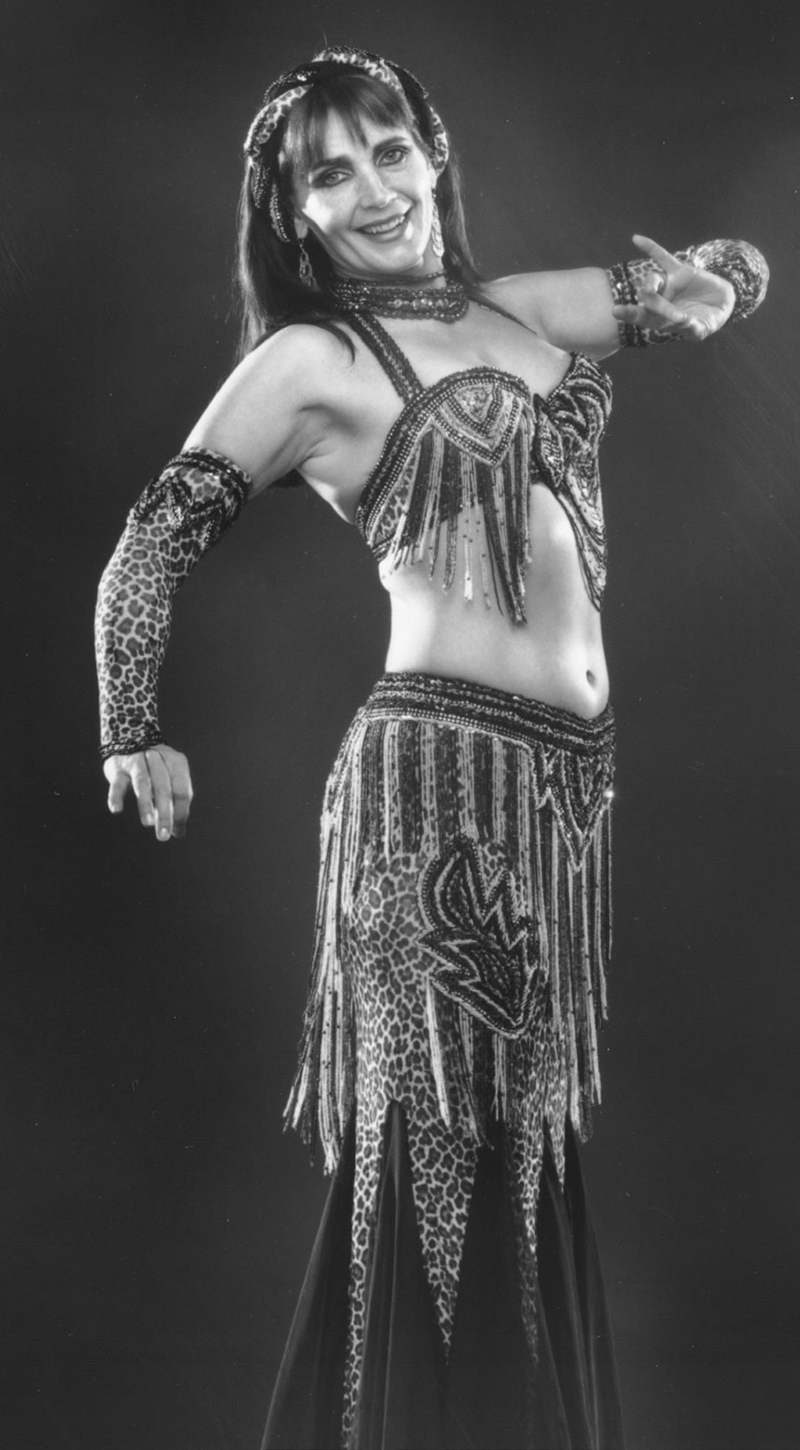

Sheikatt dancer

Known as Raqs asSharqi, or Dance of the East, this urban form of the dance, considered more sophisticated than the folkloric, is performed in public by a solo professional dancer, and is generally improvised. It represents her personal interpretation of the music. It is accompanied by an urban orchestra that often includes the addition of Western instruments and electronics. This style is most recognizable to Westerners, often represented stereotypically as "belly dance" in movies and on television.

Today, dancers in both the Middle East and the United States are experimenting with new ways of presenting Arab dance, marrying the costumes, movements, music, and folktales of the Middle East with choreography techniques, staging, and the magic and technology of the Western stage. Like all great dance traditions, Arab dance is a living art form that is adapting and changing while staying true to its heritage.

The earliest records of Middle Eastern dance are found in the tomb paintings of pre-Pharonic Egypt and the writings of Roman travelers. Dance and music flourished during the Golden Age of classical Islamic civilization, in the 8th through the 12th centuries.

Over the centuries, distinct styles have developed in different social classes among the professional performers in each class. Lower-class dancers at street festivals were known for their raw, earthy style and folk instrumentation, while urban professional and court dancers refined their movements into a graceful and sophisticated art, accompanied by a classical orchestra, known as a Tahkt.

During the 1920s and 1930s, group choreography became popular for the first time as the dance we know today. Raqs asSharqi began to develop in the Casino Opera, in Cairo, operated by Badia Masabni. Dancers created extravagant numbers for film and television. The rise of Arab nationalism in the 1950s led many countries to create national folklore troupes, bringing the dance to more stages, clubs, movies, and television.

Always a component of social life, dance’s popularity as a public performance has waxed and waned many times over the years. Only professional dancers perform for the general public. Censorship and a conservative climate occasionally restricts some traditional movements of the dance, as well as the manner in which it is presented. In the United States, dancers perform in theaters, clubs, restaurants, and at family celebrations in the Arab-American community such as birthdays, Eid festivities, and weddings.

Facial Expressions are a vital component of the dance. Arabic poetry often comments on how the eyes, eyebrows, and face as "beautiful as the moon" express emotions. The expression should match the emotions of the music—not forced, but sincere.

Hair is usually covered for folkloric dances and uncovered for professional dance styles. Dancers in the Persian Gulf region and North Africa may toss their hair in time to the music.

Hands in Arab classical dance are just that - hands. They do not represent anything else. Delicate hand movements ornament the dance. Some folkloric dances use animal imitative hand movements such as birds flying. A professional dancer may also play the rhythm of the music on her sagat (finger cymbals).

Arms in classical style create a frame that draws the eye to the isolated movements of the hips. They traditionally move in sinuous, snake-like fashion, or are held in graceful curves around the body. Recently, some Western straight arm stylings have been incorporated into Raqs asSharqi.

Torso - Unlike classical ballet, which focuses on moving the limbs in intricate patterns and lines, Middle Eastern dance focuses the viewer’s gaze on the torso - the region of the body from the shoulders to the hips - because this is where the rhythms and ornamentations are most frequently displayed. Don’t be shy - go ahead and look at the dancer's torso! Remember that the point is not to expose the body and titillate the audience; it's to illustrate the music and rhythms, and express the universal joy of movement.

Upper Torso - A dancer can express a particular rhythm by lifting and dropping her sternum or rib cage, or she may use the rib cage to fluidly undulate the spine.

Belly - The belly generally moves with the spine in a rippling, fluttering, or undulating motion. The abdominal band may move slowly or quickly depending on the tempo of the music. Isolated movements of the abdominal band are most commonly seen in a novelty act in the circus, and are not commonly used in Raqs asSharqi.

Hips - In classical dance, when in doubt, look to the dancer's hips! There is a vital relationship between the hips and the drums, because the hips should move in time to the music's rhythm. Folkloric dances may or may not involve hip movements.

Legs - Although the lines of the torso are visible, the legs are the engine of the hip movements, and it is traditionally considered inappropriate to display the legs. In folkloric dance, they are usually covered.

Feet - Unlike classical ballet, the point of Middle Eastern dance is not to move the body through space, it is rather to embody the music. Group dances may move about the room with quick and delicate steps, and yet a solo dancer generally covers less space. Feet are often flexed in contact with the floor, rather than pointed, to facilitate weighted movement.

Costumes - In Raqs asSharqi, colorful fabrics and shiny beads draw the eye to where the rhythm is being expressed, especially the hips! Veils add a flowing or floating quality to the dancer’s movements. Veils were introduced to the dance in about the 1920s. Folkloric dance costumes reflect the area, region, or tribe where the dance originated.

Watch us dance!

Middle Eastern music is a living tradition that has roots in the ancient civilizations of the Middle East. It echoes the court and folk music of Sumeria, ancient Egypt, Arabia, the Ottoman Empire, Andalusia, and Persia. The resulting music traditions are deep, varied, and evolving, as each generation innovates while honoring the forms and work of the past.

Watch the Georges Lammam Orchestra play for us!

Maqamat - The Basic Building Block

Middle Eastern music is based on the maqam system. A maqam roughly corresponds to a Western musical scale; it's a system of intervals. For example, where a Western musician might perform Pachelbel’s Canon in D (a canon - a classical form - played in the key of D major), a Middle Eastern musician might perform a Sama'i Kurd Shaheen (sama'i is a classical form, played in the maqam Kurd and composed by Simon Shaheen). A composition can begin in one maqam and shift to others during the course of the song. There are at least 24 popular maqamat (plural of maqam), developed over thousands of years of musical history. A maqam tells a musician what the correct intervals are between the notes of a scale, and which notes should be emphasized. Often, the notes of a scale lie only a quarter-step apart, rather than half-steps apart.

Rhythm

Middle Eastern music is often polyrhythmic, meaning contrasting rhythms may overlap, creating a rich base of percussion. The drummer may be playing one rhythm, the violinist another, the riq (tambourine) player a third, while the dancer stays with the drummer on her sagat (finger cymbals), and all are woven together into a tapestry of sound.

Here is Karim Nagi demonstrating the rhythms of the Levant.

Improvisation

Middle Eastern musicians frequently perform taqsim (the art of improvisation). Taqasim (pl) may be woven into existing compositions - similar to a guitar riff in the middle of an American rock song - or played as an art in themselves, as in the Arabic classical tradition. In urban popular music, musicians begin with a well-known melody, a maqam, or a simple collection of notes, then embellish it in a free-flowing manner. The mark of a true artist lies in his or her ability to improvise in music, poetry, song, and dance.

Ornamentation

Often, Middle Eastern music involves ornamentation. In the same way a dancer’s delicate hand gestures ornament her dance, a musician’s style may embrace and color individual notes. Ornamentation includes the use of grace note, trills, runs, arpeggios, "bending" a note, and other techniques. To draw a parallel, imagine singing a simple child’s melody like "Three Blind Mice." Then imagine how a jazz musician might play with the song, stretching out certain notes or adding syncopation, improvising a theme derived from the notes. One may still recognize the basic melody, yet the musician has put his or her stamp of interpretation on it. Both improvisation and ornamentation allow musicians to express their individual style within traditional forms.

Call and Response

Middle Eastern music frequently employs a call-and-response form in which an instrument plays a phrase and another instrument responds, creating a musical conversation. The lead and responding instrument will change throughout the composition. There is also call-and-response between singer and instruments, dancer and drums, and dancer and instrumentation.

Tabla - A hand drum, shaped somewhat like a goblet, traditionally made of clay and covered by a goatskin head. The tabla is the heartbeat of Middle Eastern music, as its beat keeps time for the other members of the orchestra. This drum is sometimes referred to as a durbakke or the durbakka, or in the West, as a doumbek (an onomatopoetic word based on the bass sound - dum, and the treble sound - tek).

Tar - A large, round frame drum, similar to the Irish bodhran without the internal crossbars, as the frame drum is held by the frame. The tar is used mainly in popular and folk music and is also referred to as the duff or, in North Africa where it has snare, the bendir.

Riq - An Arab drum, the riq is played by striking both the fish-skin head and the cymbals that surround it. It resembles a tambourine. Huge oversized ones, often seen in Egyptian weddings, are called mazhar.

Sagat - Small finger cymbals, similar to a flamenco dancer’s castanets. Sagat (or Turkish ziller) are played on the thumb and middle finger of both hands and are always associated with professional dancers. A dancer or musician plays the basic rhythm of the music on sagat, and may improvise syncopations where appropriate.

Oud - A short-necked, pear-shaped string instrument, the ancestor of the European lute. (Say both words aloud, and you’ll hear the relationship.) Sometimes beautifully ornamented with mother-of-pearl, the oud was traditionally made of the wood of a fruit tree and plucked with an eagle feather. (Today’s musicians use a plastic plectrum or pick.) The sound is warm and full and deep.

Kanun - A stringed instrument similar to the zither, the kanun may have as many as 72 strings, which are plucked by rings fastened to the musician’s fingers. The kanun has a delicate, intricate sound, brighter and seemingly faster than the oud. It has moveable bridges, so the player can change maqamat quickly.

Nai - A hollow reed flute, the nai has the haunting, breathy quality that Americans often associate with Arab music. Because reed flutes cannot be tuned to the different maqamat, a nai player carries flutes of many different sizes. Nai is the melodic instrument of the dervish sects.

Violin - Familiar to American audiences, the Western violin (with Arab tuning) was introduced to the Middle Eastern orchestra only recently, in late 19th or early 20th century. The violin is frequently the lead or responding instrument in a traditional call-and-response. Because of its resemblance to the human voice, the violin is capable of expressing tremendous emotion. The traditional violin-like instrument, usually played on the knee, is called kemenje.

Singer - The singer plays a vital role in both traditional and classical Arab music, due to the importance of the lyrics. A classical Arabic vocalist can present an entire evening of sung poetry. As in Western music, singers exist in a variety of styles: folk, country urban popular and standards, as well as classical. The singer’s role is to bring the poetry to life through vocal techniques that evoke the emotions.

Other traditional instruments include the tabl beledi, a large bass drum played in Southern Egyptian folk music; the mizmar, an oboe-like reed instrument; the mijwiz, a double-reed instrument with a droning sound; and the rababa or rebec, a two-stringed fiddle held upright on the knee.

Modern instruments such as electric guitar, bass, accordion, saxophone, clarinet, organ, piano, silver flute, cello, drum kit, and even drum machine and synthesizers are common in today’s pop music. Like all great musical traditions, Arab music is a living art form that is adapting and changing while attempting to stay true to its heritage.